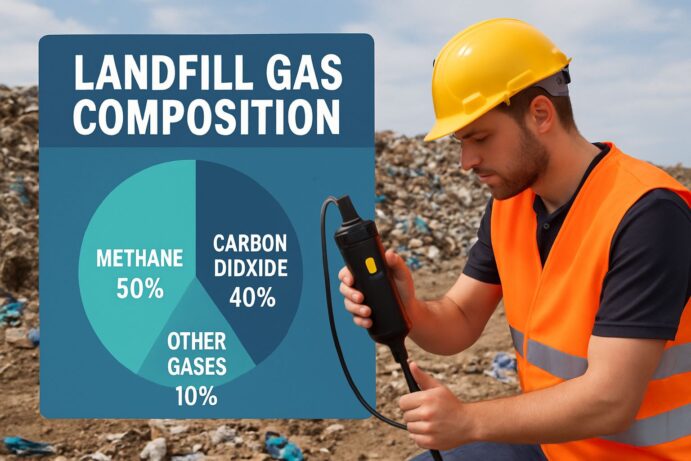

Landfill gas (LFG) is primarily a mixture of methane CH4 and carbon dioxide CO2, typically making up 90-98% of the volume, with varying concentrations around 50% methane and 50% carbon dioxide during peak production, although this varies significantly with landfill age and waste type. It also contains smaller amounts of nitrogen, oxygen, water vapour, and trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg smell), benzene, and toluene, which can pose health risks and odours.

Main Points

- Landfill gas is usually made up of 45-60% methane and 40-60% carbon dioxide, with trace elements that can include harmful VOCs and emerging contaminants like PFAS

- Gas composition analysis is key for environmental monitoring, regulatory compliance, and identifying potential energy recovery opportunities from methane

- The four phases of bacterial decomposition significantly alter gas composition over time, with peak methane production occurring in Phase IV

- Factors affecting landfill gas production include waste composition, moisture content, temperature, and landfill design factors

- Modern landfill gas analysis techniques range from simple field instruments to sophisticated laboratory methods capable of detecting compounds at parts-per-billion levels

Understanding what's hiding beneath the surface of our landfills is more than just academic curiosity—it's necessary environmental intelligence. When it comes to effectively managing waste facilities, comprehensive landfill gas composition analysis provides the vital data that environmental scientists need for regulatory compliance, climate impact assessment, and potential energy recovery operations.

The Unexpected Composition of Landfill Gas: What's Really Lurking?

Landfill gas is more than just the “smell of trash.” It's a complex blend of hundreds of different compounds that are created through a variety of biological and chemical processes. This blend changes significantly over time as the waste breaks down, creating a constantly changing environmental issue that requires advanced monitoring methods.

By analysing this complicated mixture of gases, we can gain insights into not only how effective waste management practices are, but also what potential environmental and health impacts there may be.

Methane and Carbon Dioxide: The Main Players

The two major components of landfill gas are methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂). Methane typically accounts for 45% to 60% of landfill gas by volume, while carbon dioxide contributes 40% to 60%.

hese percentages are indicative of the final stage of waste decomposition, which can take a long time to achieve. The balance between these two gases is a crucial measure of how efficiently waste is decomposing and how mature a landfill is.

The importance of this composition lies in the difference in climate impact. Methane is about 28-36 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period, which makes landfills one of the biggest human-made sources of methane emissions worldwide.

But this also provides a chance—the high methane content makes landfill gas a possible energy source when properly captured and processed. For more insights, explore the trace gases in landfill gas and their potential uses.

“landfill gas with time.JPG …” from commons.wikimedia.org and used with no modifications.

Small Components, Big Impact

Apart from the two main components, landfill gas consists of a variety of trace components. Despite their relatively small quantities, these components can have significant effects on the environment and health. They include nitrogen (0-5%), oxygen (0-1%), hydrogen (0-1%), and hydrogen sulfide (0-1%). These components affect the chemical behavior of the gas and its potential uses.

The non-methane organic compounds (NMOCs) are of particular concern. While they usually make up less than 1% of landfill gas, they can include substances that are potentially harmful, such as trichloroethylene, vinyl chloride, and benzene.

These compounds can come from chemical reactions within the landfill itself, industrial wastes, and household products. Many of these compounds exceed health-based regulatory thresholds, even at concentrations of parts per billion, and need careful management strategies and monitoring.

Typical Composition of Landfill Gas at Phase IV Stability

Methane (CH₄): 45-60%

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂): 40-60%

Nitrogen (N₂): 2-5%

Oxygen (O₂): 0.1-1%

Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S): 0-1%

NMOCs (combined): 0.01-0.6%

The Science of How Landfill Gas Forms: Waste Decomposition Explained

Landfill gas doesn't just appear out of nowhere—it is the result of intricate biological and chemical processes taking place within the waste mass. Understanding how these processes form landfill gas is key to predicting gas production rates and composition, which in turn directly influences management strategies.

Three main processes generate landfill gas: bacterial decomposition, chemical volatilisation, and direct chemical reactions between waste components.

- Bacterial decomposition – responsible for producing the majority of methane and carbon dioxide

- Volatilisation – the process by which liquid or solid chemicals convert to vapour form

- Chemical reactions – direct interactions between chemicals disposed of in the waste

- Physical transport – movement of existing gases from the atmosphere into the landfill

The Four Phases of Bacterial Decomposition

Bacterial decomposition in landfills follows a predictable progression through four distinct phases, each characterised by different microbial communities and resulting gas compositions. Phase I begins immediately after waste placement, with aerobic bacteria consuming available oxygen and producing primarily carbon dioxide. This phase typically lasts only a few days to weeks until available oxygen is depleted, as discussed in landfill gas extraction well design.

“Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP …” from 19january2021snapshot.epa.gov and used with no modifications.

Phase II starts as the oxygen supply dwindles, creating anaerobic conditions. This phase is dominated by acid-forming bacteria that break down complex organic molecules into simpler compounds, including volatile fatty acids. The gas composition changes significantly during this phase. Carbon dioxide levels may rise to 70%, hydrogen may be present in small quantities (5-10%), and the amount of nitrogen from trapped air decreases gradually.

Phase III is when the landfill starts to become methanogenic, which means that methane-producing archaea start to grow. These specific microorganisms use hydrogen and carbon dioxide to create methane, and the gas composition starts to change to the mix typically seen in mature landfills. This transitional phase can last anywhere from a few months to a few years, depending on the conditions of the landfill.

Decomposition enters Phase IV when the landfill gas composition and production rates stabilise, usually reaching the balance of 45-60% methane and 40-60% carbon dioxide that was mentioned earlier.

This mature phase can last for decades, with gas production slowly decreasing over time. The duration of this phase is why landfills continue to be active sources of methane long after they have closed, and why monitoring programs need to continue long after a facility has stopped being active.

Within a single landfill, different parts of the waste mass may be in different decomposition phases at the same time, resulting in a heterogeneous gas composition that varies spatially. This complexity underscores the need for a comprehensive gas monitoring network that takes samples from multiple locations to develop an accurate picture of the overall landfill gas composition and production dynamics.

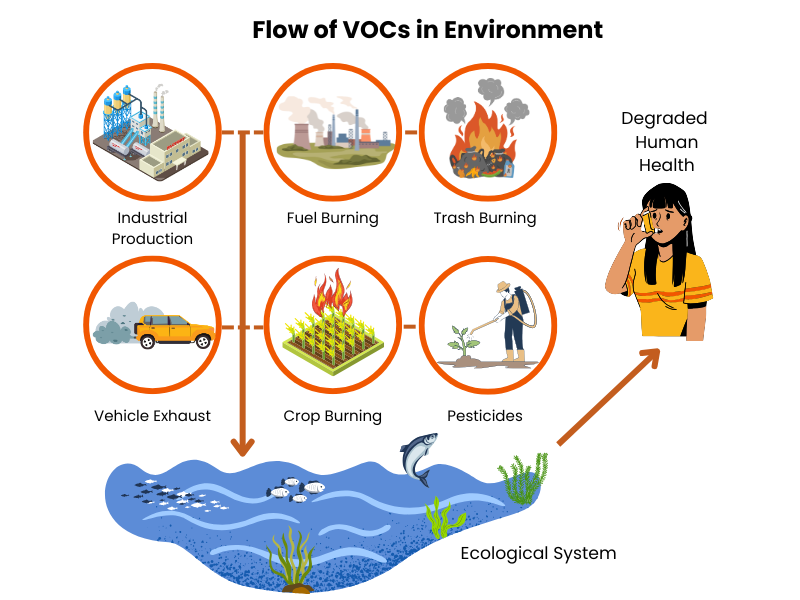

Chemical Evaporation Process

Although bacterial decomposition is responsible for most of the landfill gas, the chemical evaporation process plays a large role in the trace compound profile that can harm the environment. Evaporation happens when chemicals in liquid or solid waste turn directly into gas without the help of bacteria. This process is especially crucial in understanding why volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other dangerous air pollutants are present in landfill gas.

Several factors influence the rate of volatilisation, such as the compound's vapour pressure, the temperature of the environment, the pressure conditions inside the landfill, and the physical properties of the surrounding waste matrix. Higher temperatures speed up volatilisation, which is why VOC concentrations in landfill gas often rise during warmer seasons.

Compounds with higher vapour pressures, such as acetone, benzene, and many chlorinated solvents, volatilize more readily than those with lower vapour pressures. For more insights on managing these emissions, explore landfill gas emissions control strategies.

What Influences Gas Production Rates?

There are several environmental and operational factors that can affect how much gas is produced and what it's composed of. The most important of these factors is the composition of the waste. Landfills that receive a lot of organic waste (like food waste, yard trimmings, and paper products) tend to produce more methane and at faster rates.

Nowadays, we can predict how much gas will be generated by a landfill by studying the waste that's coming in.

The moisture content is the “speed booster” for gas production. Landfills in humid climates or those designed as bioreactors with added moisture usually produce gas faster than dry landfills. The best bacterial activity happens when the moisture content is between 40-60% by weight, a condition that many landfills in arid regions never reach.

Temperature also greatly affects production rates, with the best methanogenic activity happening between 35-40°C (95-104°F)—temperatures that are naturally reached in the interior of large landfills through exothermic decomposition reactions.

The last set of controlling factors is determined by landfill design and operational practices. Gas generation and migration are influenced by the degree of waste compaction, cell construction methods, cover systems, and leachate management.

The natural gas profile is altered by modern engineered landfills with gas collection systems, which create pressure differentials that affect both production rates and composition throughout the waste mass.

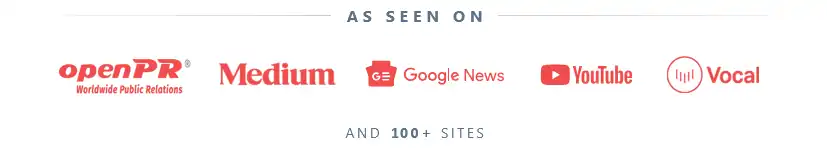

Methane: A Powerful Climate Risk and Energy Resource

Landfill gas is a significant source of methane, which is both an environmental problem and an economic opportunity. Methane is a greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming 28-36 times more than CO₂, and emissions from landfills account for about 17% of human-related methane emissions worldwide.

However, this powerful gas also contains about 50% of the energy value of natural gas, so landfills could be a source of renewable energy if they are managed correctly. For more information on managing landfill emissions, check out this article on gas monitoring at landfills.

The Importance of Methane Over CO₂

What makes landfill emissions so impactful on the climate is not just the amount of gas, but what the gas is made of. Carbon dioxide usually makes up about half of landfill gas by volume, but methane is responsible for about 90% of the climate impact because it has a much higher potential for global warming.

This is why reducing methane can have a much bigger effect on the climate than the cost of implementing the reduction strategies would suggest. For more information on managing emissions, explore landfill gas emissions control.

Methane's relatively short atmospheric lifetime of about 12 years, compared to the centuries-long persistence of carbon dioxide, is another important factor. This shorter lifespan makes methane mitigation strategies particularly effective in delivering near-term climate benefits.

By reducing methane emissions now, we can achieve significant atmospheric concentration reductions within decades rather than centuries, potentially helping to avoid critical climate tipping points.

“Waste sector solutions | Climate …” from www.ccacoalition.org and used with no modifications.

Transforming Waste Gas into Useful Energy

Landfill gas, with its high methane content, is a potential renewable energy source if it is appropriately gathered, processed, and used. Modern landfill gas-to-energy (LFGTE) systems can transform this waste product into electricity, pipeline-quality natural gas, or compressed natural gas for vehicles.

The financial feasibility of these projects is heavily reliant on precise gas composition analysis, as contaminants can harm equipment and decrease energy conversion efficiency.

Monitoring Changes in Concentration Over Time

The composition of landfill gas isn't fixed—it changes over the course of a site's active and post-closure lifespan. To keep track of these changes, regular sampling and analysis are necessary to record trends in both primary components and trace compounds. Spotting changes in composition early on can signal changes in decomposition conditions, potential failures in the cover system, or the need to tweak the operation of the gas collection system.

Long-term data monitoring shows that methane concentrations typically follow a predictable curve. They rise through the first several years of waste placement, plateau during active decomposition phases, and then gradually decline over decades. The rate of this decline varies significantly based on site-specific factors.

This makes individualised monitoring essential for accurate gas production modelling and management planning.

What You Need to Know About Hazardous Trace Chemicals

While methane and carbon dioxide are the main components of landfill gas, the trace elements often pose the most serious health, safety, and environmental risks. These compounds are found in concentrations ranging from parts-per-million to parts-per-billion, but they can exceed health-based thresholds even at these low levels.

Thorough landfill gas analysis must not only characterise the main composition but also this “long tail” of trace compounds that may necessitate specialised treatment or monitoring methods.

Understanding Non-Methane Organic Compounds (NMOCs)

Non-methane organic compounds are a group of hundreds of different chemicals that can be found in landfill gas. These include alkanes, aromatics, chlorinated hydrocarbons, oxygenated compounds, terpenes, and siloxanes. Despite only making up between 0.01% and 0.6% of landfill gas by volume, NMOCs are responsible for most of the regulatory concerns and treatment challenges associated with landfill gas.

NMOCs are produced from three main sources:

- the direct volatilisation of chemicals that have been disposed of,

- byproducts of the decomposition of waste, and

- chemical reactions that take place within the landfill environment.

The particular profile of NMOC can vary significantly between landfills, and this depends on the composition of the waste, its age, and the local environmental conditions. The NMOC signatures that you will typically find in municipal solid waste landfills are different to those that you will find in construction and demolition landfills or industrial waste facilities.

It is crucial to know this fingerprint as it allows for the design of appropriate gas treatment systems and it also allows for the evaluation of potential environmental impacts. Some of the NMOCs that are commonly found include benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylenes (these are BTEX compounds), vinyl chloride, and a variety of chlorofluorocarbons.

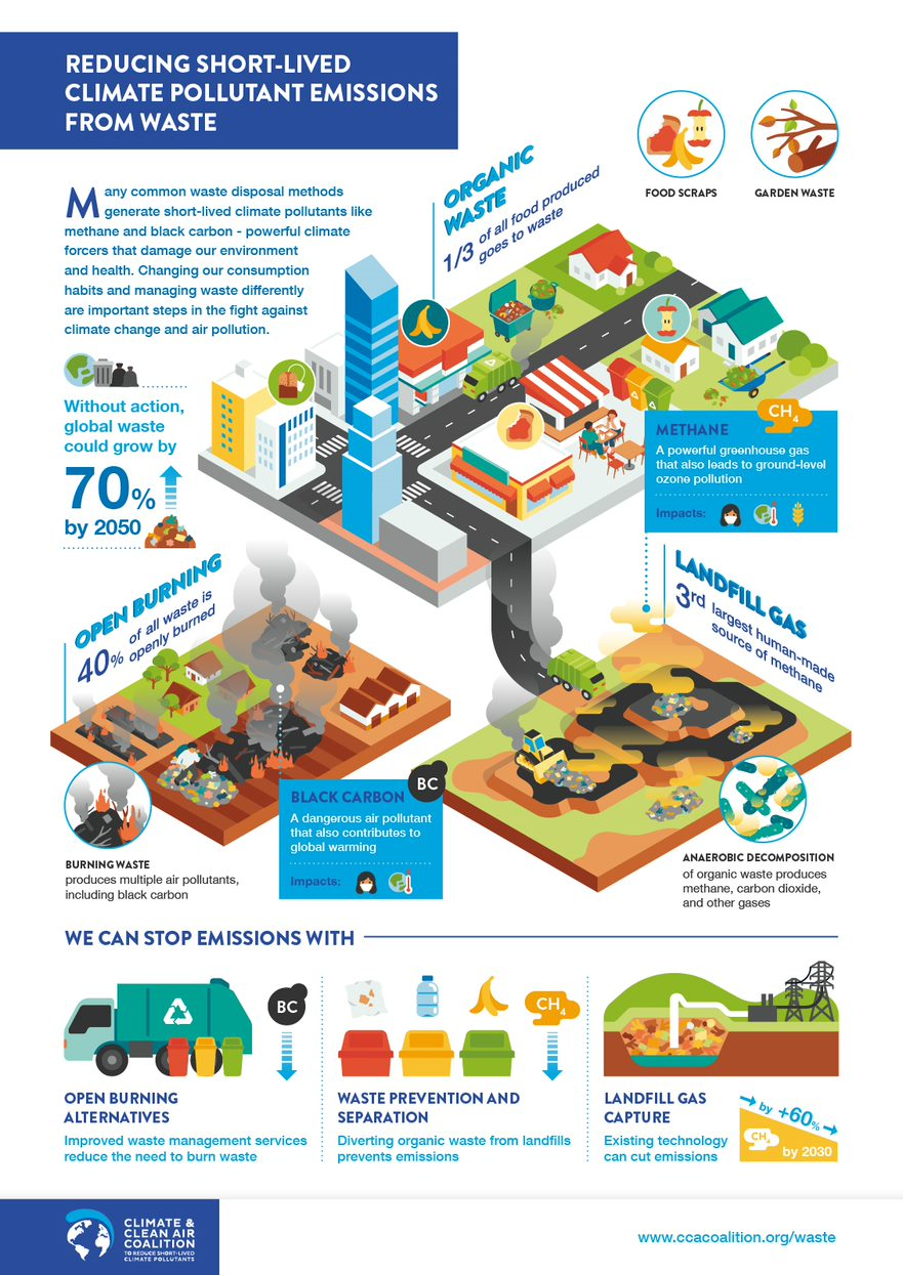

“non-methane volatile organic compounds …” from acp.copernicus.org and used with no modifications.

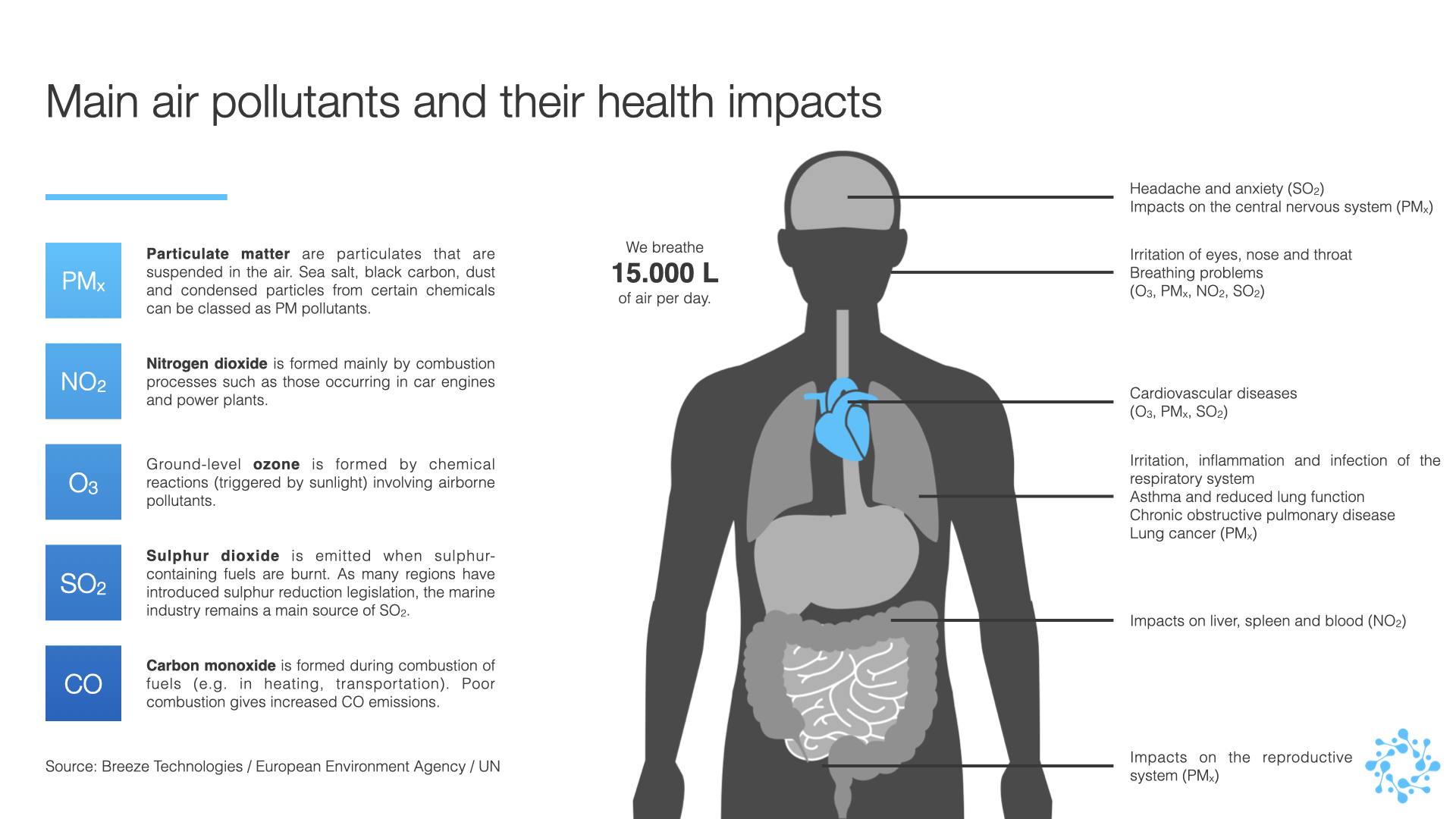

Health Issues Related to VOCs and Hazardous Air Pollutants

Landfill gases contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which pose serious health and environmental problems that go beyond the impact on the climate. When these compounds are released into the atmosphere, they can contribute to the formation of photochemical smog, worsening regional air quality.

VOCs such as benzene, vinyl chloride, and carbon tetrachloride are known or suspected carcinogens that can have severe health effects even at very low exposure levels if their concentrations are high enough.

“air pollutants …” from www.breeze-technologies.de and used with no modifications.

There are several ways that people can come into contact with these compounds, including directly breathing in landfill gas emissions, vapours seeping into nearby buildings, and the compounds travelling through the soil into groundwater resources.

The risk level is determined by a variety of factors, such as the specific compounds that are present, how concentrated they are, how long the exposure lasts, and the individual's susceptibility.

Current regulatory standards, such as the Clean Air Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, have set strict limits on how much of these hazardous air pollutants landfills can emit, which is why it is necessary to perform a detailed composition analysis to prove compliance.

“What Are Volatile Organic Compounds and …” from greencitizen.com and used with no modifications.

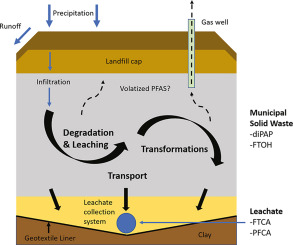

The Growing Worry of PFAS in Landfill Gas

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are some of the most difficult emerging pollutants in landfill settings. These highly durable man-made chemicals have been extensively used in consumer goods, from non-stick cookware to water-resistant textiles and firefighting foams.

Recent studies have found PFAS compounds in landfill leachate and, at low levels, in landfill gas, raising new worries about previously unknown exposure routes.

For further insights, explore the trace gases in landfill gas and their implications.

The evaporation process for these compounds, which are usually not volatile, is still being studied. However, the most popular theories suggest that they may be carried by particulate matter in the gas stream or by aerosol formation within collection systems.

There are many analytical challenges. To detect these compounds in landfill gas, you need a special sampling device and high-resolution mass spectrometry techniques, which few commercial laboratories currently offer.

The regulations for PFAS in landfill gas are still being developed, creating a lot of uncertainty for landfill operators and environmental monitors.

“PFAS in municipal solid waste landfills …” from www.sciencedirect.com and used with no modifications.

Methods for Gas Sampling and Analysis

Correctly identifying the components of landfill gas calls for a meticulously planned program for sampling and analysis. A single analytical method cannot identify every compound of interest, so a layered strategy is required that combines field screening methods with laboratory confirmatory analyses.

The network of sampling locations must take into account the spatial variability within the landfill, while the frequency of temporal sampling must take into account seasonal variations and operational changes that affect gas production.

On-Site Monitoring Tools

Portable instruments used in the field give immediate data on the main gas components and some trace compounds. Infrared analysers are good at detecting methane and carbon dioxide, usually with an accuracy of ±3% for these main components.

Photoionisation detectors (PIDs) and flame ionisation detectors (FIDs) measure total VOCs but can't tell the difference between individual compounds.

Electrochemical sensors can detect specific gases like hydrogen sulfide, oxygen, and carbon monoxide, but their selectivity and sensitivity can vary.

Advanced portable gas chromatographs can detect and measure individual compounds with less precision than lab instruments. These systems usually separate and identify between 10 and 20 target VOCs with detection limits in the parts-per-million range.

This is enough for compliance monitoring, but often not enough for a thorough health risk assessment. As these systems continue to become smaller and more portable, they are gradually becoming more similar to lab-grade instruments in terms of their capabilities.

Methods of Lab Analysis

The most sensitive and specific way to characterise landfill gas is through lab analysis. The best way to identify VOCs is with gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC/MS), which can detect hundreds of compounds at parts-per-billion levels.

Several specialised methods target different classes of compounds: EPA Method TO-15 for VOCs, Method TO-11A for aldehydes and ketones, and Method TO-13A for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. For emerging contaminants like PFAS, you may need to use high-resolution mass spectrometry techniques such as quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) or Orbitrap systems.

Collecting samples for lab testing can be complex. There are several methods for doing this, including whole-air sampling in passivated canisters, sorbent tube collection, and cryogenic concentration. The best method depends on what you’re testing for, how much of it you expect to find, and the conditions in the field where you’re testing.

You also need to document the chain of custody and follow sample preservation protocols to make sure your data is accurate. This is especially important if you need to show that you’re following regulations.

Continuous versus Periodic Monitoring Methods

Deciding between continuous and periodic monitoring depends on the goals of the monitoring, the regulatory requirements, and the resources available. Continuous monitoring systems provide real-time data on selected parameters, which allows for an immediate response to changing conditions and a detailed analysis over time.

These systems usually focus on major components such as methane, carbon dioxide, and oxygen, as well as operational parameters like flow rate, temperature, and pressure.

Advanced continuous systems may include automated calibration routines and the ability to transmit data remotely for integration with facility management systems.

Difficulties in Understanding Data

It takes a certain level of knowledge in both technical analysis and regulatory context to transform raw analytical data into useful information. When evaluating compliance or risk implications, results must consider the potential for sampling and analytical variability, potential interferences, and method detection limits.

Common Landfill Gas Interpretation Challenges

- Spatial variability: 30-50% concentration differences between monitoring points

- Seasonal variations: 15-25% higher methane production in summer months

- Barometric pressure effects: Emissions can increase 2-5× during falling pressure

- Background contamination: Ambient VOCs can introduce false positives

- Compound interactions: Chemical reactions between components during sampling

Setting the right data quality objectives before starting a monitoring program helps ensure that the results will meet their intended uses. For compliance demonstrations, analytical methods must meet specific regulatory requirements for detection limits, precision, and accuracy.

For engineering applications like energy recovery system design, the focus shifts to accurately quantifying major components and contaminants that could affect equipment performance. The presence of silicon, for example, will be measured due to its ability to form inside gas engines and can dramatically reduce equipment life.

Tools for visualising data have grown in significance for understanding complex data sets of compositions. Three-dimensional maps of concentration gradients across a landfill can pinpoint areas that need concentrated management.

Analysis of time-series can uncover trends that might be linked with changes in operation, seasonal changes, or the breakdown of gas collection infrastructure.

By combining data on the composition of landfill gas with other environmental monitoring parameters, we can gain a deeper understanding of how a facility is performing. Looking at the chemistry of leachate, settlement rates, surface emissions, and gas composition together can reveal what's happening inside the waste mass in a way that looking at any one data stream on its own cannot.

The Future of Landfill Gas Management

Landfill gas management is set to become more advanced in the future. This will involve the use of more sophisticated analysis techniques, which will be combined with real-time modelling. The aim of this is to optimise environmental protection and resource recovery.

The way we understand and manage complex waste environments is set to be transformed by advancements in sensor technology, remote monitoring capabilities, and predictive analytics. The creation of standardised analysis protocols for emerging contaminants such as PFAS in landfill gas is an immediate priority.

This is something that the waste management industry and regulatory agencies need to address in order to fill the current knowledge gap.

Common Landfill Gas Questions

Landfill gas composition and management are complex subjects that often lead to questions from environmental professionals, regulators, and the public. The answers below are based on the latest scientific research and industry best practices and should help address some of the most common questions.

The following commonly asked questions aim to clarify the main ideas in landfill gas composition and analysis. They offer easy-to-access information for environmental professionals who manage these intricate waste systems.

What is the average methane production of a landfill?

The amount of methane produced by a landfill can vary greatly depending on the composition of the waste, the climate, and the design of the landfill. A typical municipal solid waste landfill will produce about 100 cubic meters of landfill gas per metric ton of waste over its lifetime, with 45-60% of that being methane.

For a medium-sized landfill that receives 1,000 tons of waste per day, this means that it will produce about 8-10 million cubic feet of methane per year during its peak years of production.

Production follows a bell curve, with it gradually increasing during the first 2-5 years after the waste is placed, maintaining peak production for 5-10 years, and then gradually declining over the course of several decades.

Is it possible to use landfill gas directly in natural gas pipelines?

Without substantial processing, raw landfill gas cannot be directly used in natural gas pipelines. The main challenges are its lower methane content (45-60% versus 95%+ for pipeline natural gas), high carbon dioxide content (40-60%), and trace contaminants that can harm pipeline infrastructure or end-use equipment.

For more information on managing these contaminants, you can explore landfill gas monitoring procedures.

Here's what you need to know about the composition of landfill gas and the chemicals it contains:

- Siloxanes are removed to prevent silica deposits from forming in combustion equipment

- Hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur compounds are removed to prevent corrosion

- Moisture is eliminated to meet pipeline dewpoint specifications

- Halogenated compounds are removed to prevent the formation of acidic combustion products

- Particulate matter is filtered out to protect equipment

Landfill gas can be upgraded to renewable natural gas (RNG) that meets pipeline specifications using advanced treatment systems that use multiple technologies, such as pressure swing adsorption, membrane separation, or cryogenic processing. However, these systems have significant capital and operating costs. The economic viability of these systems depends on gas flow rates, the initial composition of the gas, and available incentives like renewable fuel credits.

Once appropriately treated, the resulting renewable natural gas is chemically the same as traditional natural gas and can be used interchangeably in all natural gas applications, from heating homes to fueling vehicles.

What are the health hazards of living near landfills?

The primary focus of health risk assessments for residents living near landfills is exposure to trace elements in landfill gas rather than the major components. Modern epidemiological studies have found little evidence of increased health risks at properly managed facilities with functional gas collection systems.

The main exposure pathway of concern is the off-site migration of VOCs through soil or ambient air, potentially reaching concentrations of concern in indoor air through vapour intrusion processes. Proper landfill design, operational practices, and monitoring programs effectively mitigate these potential risks by controlling gas migration and treating collected gas to destroy harmful compounds before atmospheric release.

For how long do landfills keep producing gas?

Even after a landfill site stops accepting waste, it continues to produce gas for a long time. It usually does this for over 30 years at rates that can be economically recovered. It is possible for it to continue production for 50 to 100 years, but this depends on the waste composition and the environmental conditions.

The production rate follows first-order decay kinetics, with about half of the total gas generation happening in the first 10 to 15 years after waste placement. Modern bioreactor landfills can speed up this timeline by optimising moisture conditions. This could potentially concentrate 80% of the lifetime gas production within 15 to 20 years.

This extended production timeline means that long-term monitoring and management strategies are necessary for decades after the site is closed.

What separates landfill gas from biogas?

While both gases are products of the anaerobic breakdown of organic substances, there are key differences between landfill gas and biogas from digesters. Landfill gas usually has lower methane concentrations (45-60%) compared to digester biogas (55-70%), and higher nitrogen and trace contaminant concentrations due to the varied waste composition and less controlled environment.

Biogas digesters operate under meticulously optimised conditions with chosen feedstocks, resulting in a more consistent gas composition and fewer contaminants. Both gases are valuable renewable energy sources, but landfill gas usually needs more comprehensive treatment before use due to its more complicated composition profile.

It's important to know the exact makeup of landfill gas for the sake of the environment, following the rules, and making the most out of resources. As we get better at analysing, we'll understand more about these complicated gas mixtures. This will let us manage them better and do a better job of keeping people and the environment safe.

Expert Insights: Future Trends in Landfill Gas-to-Energy Conversion

Landfill gas conversion holds potential as a $1.9 billion industry, yet many landfills lack gas collection. Innovations in gas collection, early installation, and real-time monitoring could cut U.S. landfill methane emissions nearly in half, addressing climate goals and boosting the renewable energy sector…

Landfill Gas Extraction Pipework Basics

This guide outlines the basic principles of all landfill gas extraction pipework, focusing on condensate management, valve selection, and system redundancy to ensure maximum methane recovery and environmental safety. Key Takeaways on the Landfill Gas Extraction Pipework Basics Condensate Management: Efficiently removing moisture is the primary challenge in maintaining gas flow. Valve Superiority: Sleeve valves […]

US Landfill Gas Resources: A Booming Green Energy Sector

Untapped U.S. Landfill Gas Resources are an Opportunity for Green Investment The American landfill gas (LFG) sector has seen a big change in recent years. It's now a key player in the country's biogas world. Even though it's only 23% of over 2,500 biogas systems now installed nationwide, it captures 72% of all biogas by […]

Landfill Gas Management Solutions

You know the tough part about landfill gas is that the problems rarely show up one at a time. Odors, off-site migration concerns, wellfield instability, and methane emissions can all trace back to the same root issue: gas is finding an easier path than the one you built for it. All this leads to the […]